Hull: The City That Would Not Die, from RIBA Journal

Hull: The City That Would Not Die, from RIBA Journal

Sunday, May 24, 2009

Monday, May 18, 2009

Tuesday, May 12, 2009

THE KINDNESS OF STRANGERS

With its chronic environmental problems, Budapest was never really going to top the list of Liveable Cities. However, if we're talking about a viable way for people to live together in an urban environment (rather than an index to help multinational corporations and Governments calculate relocation allowances), then there are certainly lessons to be learned from this fine, smoggy, congested European capital. Though your first Saturday morning gasp of fresh air on alighting the bus in the Buda Hills after a week of scuttling around Pest is second-to-none, Budapest gets a lot right.

As I've mentioned before, the early glimpse of life on the mainland gleaned from the pages of modern languages textbooks at school - where everyone wore their rucksacks on both shoulders, finished school at lunchtime, earnestly loved the Cure and played a hell of a lot of ping pong - still remains my go-to point of reference for thinking about our European cousins. Even then I knew something was wrong with our own semi-detached way of living, although I could never quite understand Marta, José and Javier's adoration for the Yellow Magic Orchestra.

High-rollers, diplomats and politicians here in Budapest take palatial villas with exquisitely-landscaped compounds in the hills at Normafa or Roszadomb (prime Saturday morning ogling, if you're ever in the vicinity). However, Budapestis, by-and-large, live in flats - be they in the glorious, tumble-down apartment blocks of central Pest or the slightly-less-glorious panel houses of Újpest, Újpalota or Kelenföld. And it works rather well. Although Budapest is a capital city, its thoroughly walkable (much of the metro system in the centre of the city is as surplus to requirements as the Covent Garden-Leicester Square stretch of the Piccadilly Line), has distinct, well-amenitied neighbourhoods and - most startlingly - there are actually people walking about on the street after 6pm! I'm not talking about the rather formal promenade of cities like San Sebastian or Seville, but streetlife here (in all its strange, unctuous forms - when Google Street View finally makes it here, they'll be prime ogling there too) continues long after close-of-play.

This last part has long been a problem for provincial cities in the UK (and for once, I mean that in the most London-centric way possible). We just don't seem to get the hang of getting up and having a walk around. In Norwich and Hull (the cities that, for my sins, I feel most able to comment upon), come six o' clock inhabitants would flee to their homes to get tucked up safe away from, well, all the people who live there. If you dawdle, or, say, fancy a stroll, you face a O.K. Corral of paranoia with that tough-looking chap walking in the opposite direction down the High Street. In fact, if you were feeling a bit Daddishly pithy, you might say that under these circumstances you could begin to see the point of Bill Drummond and Iain Sinclair's psychogeographic simonizing of perambulation.

It's unfortunate that talk of declining community values in Britain should traditionally have a Littlejohnish bent, as Mr Tolerance himself would be the last likely tenant in the experimental mixed housing schemes that are valiantly attempting to counter the complex of problems around society and sustainability in the UK. Elsewhere, with the growth of riverside developments - albeit with the barf-inducing rebranding of flats as European-style apartment living - we seemed to be getting the idea. However, the economic crisis has meant fewer are willing to invest in - or, indeed, afford - in a pricy single storey. What's more, whilst a sizeable proportion of British people still live in the mistakes thrown up during post-war redevelopment, there will always be a deep-rooted suspicion of high density housing. It remains to be seen whether you really can prise the Englishman from his semi-detached castle.

As I've mentioned before, the early glimpse of life on the mainland gleaned from the pages of modern languages textbooks at school - where everyone wore their rucksacks on both shoulders, finished school at lunchtime, earnestly loved the Cure and played a hell of a lot of ping pong - still remains my go-to point of reference for thinking about our European cousins. Even then I knew something was wrong with our own semi-detached way of living, although I could never quite understand Marta, José and Javier's adoration for the Yellow Magic Orchestra.

High-rollers, diplomats and politicians here in Budapest take palatial villas with exquisitely-landscaped compounds in the hills at Normafa or Roszadomb (prime Saturday morning ogling, if you're ever in the vicinity). However, Budapestis, by-and-large, live in flats - be they in the glorious, tumble-down apartment blocks of central Pest or the slightly-less-glorious panel houses of Újpest, Újpalota or Kelenföld. And it works rather well. Although Budapest is a capital city, its thoroughly walkable (much of the metro system in the centre of the city is as surplus to requirements as the Covent Garden-Leicester Square stretch of the Piccadilly Line), has distinct, well-amenitied neighbourhoods and - most startlingly - there are actually people walking about on the street after 6pm! I'm not talking about the rather formal promenade of cities like San Sebastian or Seville, but streetlife here (in all its strange, unctuous forms - when Google Street View finally makes it here, they'll be prime ogling there too) continues long after close-of-play.

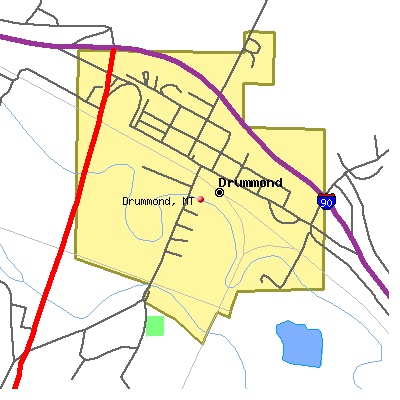

This last part has long been a problem for provincial cities in the UK (and for once, I mean that in the most London-centric way possible). We just don't seem to get the hang of getting up and having a walk around. In Norwich and Hull (the cities that, for my sins, I feel most able to comment upon), come six o' clock inhabitants would flee to their homes to get tucked up safe away from, well, all the people who live there. If you dawdle, or, say, fancy a stroll, you face a O.K. Corral of paranoia with that tough-looking chap walking in the opposite direction down the High Street. In fact, if you were feeling a bit Daddishly pithy, you might say that under these circumstances you could begin to see the point of Bill Drummond and Iain Sinclair's psychogeographic simonizing of perambulation.

It's unfortunate that talk of declining community values in Britain should traditionally have a Littlejohnish bent, as Mr Tolerance himself would be the last likely tenant in the experimental mixed housing schemes that are valiantly attempting to counter the complex of problems around society and sustainability in the UK. Elsewhere, with the growth of riverside developments - albeit with the barf-inducing rebranding of flats as European-style apartment living - we seemed to be getting the idea. However, the economic crisis has meant fewer are willing to invest in - or, indeed, afford - in a pricy single storey. What's more, whilst a sizeable proportion of British people still live in the mistakes thrown up during post-war redevelopment, there will always be a deep-rooted suspicion of high density housing. It remains to be seen whether you really can prise the Englishman from his semi-detached castle.

Monday, May 11, 2009

Tuesday, May 5, 2009

THE CONVERSATION

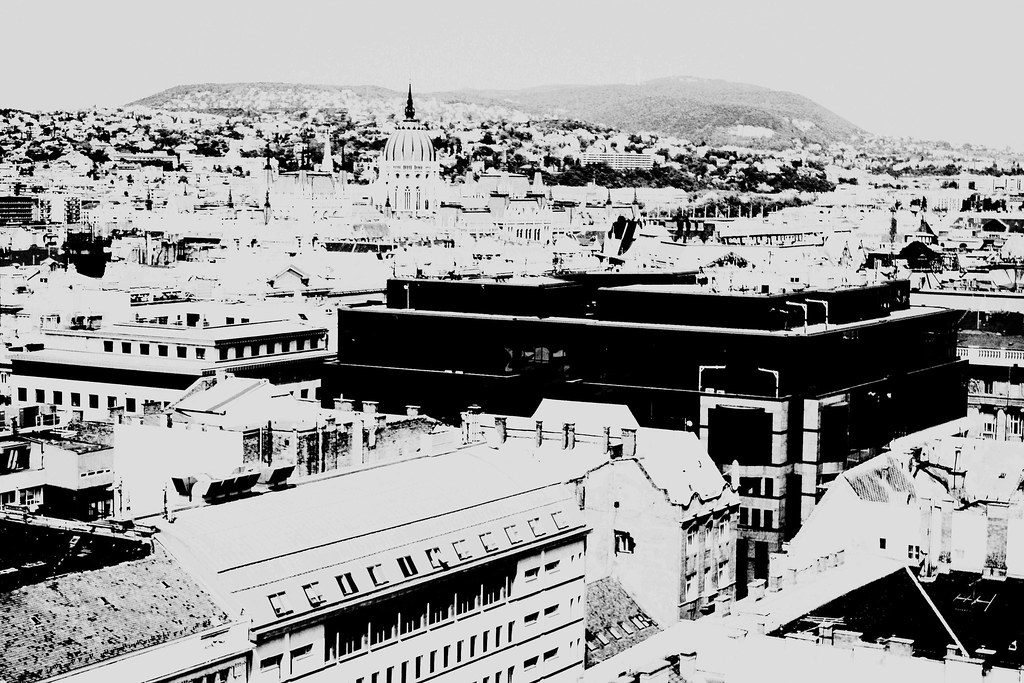

Incipient nark due to painful Burton on the stairs late last week quickly curtailed by this astonishing view from Szent-Istvan Bazilika.

Not quite Union Square, but definitely a Polanski view of the city - with iconography to match.

On Loving Angels, Instead

I leave the window open every time I go to sleep, just so she can come in. Just so she can be with me. Jack Tweed, OK! Magazine, April 7 2009

I leave the window open every time I go to sleep, just so she can come in. Just so she can be with me. Jack Tweed, OK! Magazine, April 7 2009The popular response to the death of Jade Goody from cervical cancer some weeks ago took its cues from the interminable vamp in the tabloid press in the weeks and months leading up to her death. Her very public mourning has made us feel most uncomfortable: those badly-spelt tributes on The Sun’s message boards, those cheap wreaths stacked outside St John the Baptist Church, those pinch-faced women toting half-deflated helium balloons outside her home in Upshire. Yuck, the rank whiff of British working class sentimentalism. We’re a commemorative plate away from Lady Di territory here. Thank God for The Guardian, then! Their commentary straddles – hand-wringing and superior – over the tabloid dross pile, asking just what does the death of this 27 year-old woman teach us about ourselves? Matching sub-Baudrillardian analysis (postmodern!) with touching anecdotes (poignant!), they conclude: not much, but it’s terribly sad!

However, I’m not here to take potshots at The Guardian, not today anyway. Instead I want to talk about the sudden appearance of supernatural beings in our most rational of Kingdoms. I'm talking, of course, about the angels in our midst.

Here's some rather bilious cut-and-pasting from the BBC comments board to illustrate:

Here's some rather bilious cut-and-pasting from the BBC comments board to illustrate:God bless the brand new angel and u will never forgotten u were a great woman. Jade Goody passed away to heaven as an angel. God needed another angel. R.I.P Jade. Its been a week since god blessed the sky with a new angel... the stars are shining bright for your boys Jade.

A very peculiar lexicon has emerged out of our response to these very public deaths over the last twelve years since the big one, the one that started it all, the one that we're all rather embarassed about. It's a language that is shared not only between those with the poor spelling and the Interflora wreaths, but also – curiously – those with the university degrees and respected careers in journalism who are currently employees of Richard Desmond. One arranged around some kind of quasi-religious myth, which bowdlerises its basic structure from Catholicism, its rhetoric from OK! Magazine and its iconography from Anne Geddes.

In postwar Britain, our shaky sense of the real brought a raft of moral, occultist and mystical dogma, all compensating for the decline in religious faith – those old, sacred, survival fictions. The brittle social satires of Muriel Spark, early Christine Brooke-Rose and Angus Wilson depict a nation busily crafting their own ersatz meaning-making machines. Their characters are epistemological bricoleurs, rehashing old moral systems or creating new technological and scientific cults with which to make sense of a world after rationalism, after Freud, after Einstein, de Broglie, Planck and Heisenberg. In our own, rather drab, Franklin Mint mass hysteria, in our new moral maudlinism, we too – to borrow Muriel Spark's phrase from The Comforters – are displaying our own 'turbulent mythical dimensions' under extreme duress.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)